Technical Debt Is Not Constructive

The Metaphor

Technical Debt is typically a measure of the cost of developing software. Given time pressures it is often desirable to make short term decisions in order to enable the release of value sooner. This can lead to software that is more difficult to maintain and modify - for instance it will often lack the necessary abstractions or have poor structure.

This software is often said to have a high “technical debt”. We then have to work out how to pay down this debt when we have the time to do so. This is the “technical debt” metaphor.

As a metaphor it is useful for a few reasons, one of which is that it helps us to understand the situation in a way that can be grasped by people who may not have the skills to understand the technical details.

The problem in its usage

First, lets me clear. A codebase without tests is legacy code, this is a form of negligent debt. We are not discussing bad practises here. We are discussing the cost of making change and prioritisation of different kinds of change and specifically the articulation of these things.

However, when we look at the kinds of conversations that this metaphor produces, and then the processes that are invented, then it is often unhelpful if not outright harmful.

A stakeholder has just invested a lot of money into a project. They are expecting value, and they are expecting to be able to continue to iterate on that value.

This process involves telling a stakeholder that the software is essentially not fit for purpose and that we need to pay down the debt before we can continue development. This is often used to justify why we cannot continue development as we would like to - it is essentially demanding a ransom from the stakeholders to enable us to continue development as we would like to.

This, on software that we are iterating upon causes several problems:

- We just finished software that is not fit for purpose.

- We have to convince stakeholders that we need to pay down technical debt before we can continue development.

- We have introduced a new kind of thing to be prioritised - how does this interact with other things that have been prioritised?

The first tells the stakeholder that we are not delivering value in a sustainable way, we have engaged in some form of fraud that has enabled a release but have produced a thing that we know is not fit for purpose.

The second holds them to ransom

The third makes their lives more complicated because we have not translated some kind of need into a context that they can work understand.

All of these three things are unhelpful and unnecessary.

Technical Debt enables learning earlier and faster - it is a good thing

All of these also ignore the fact that by incurring technical debt we are able to get to value faster and learn faster.

Getting to value faster is better for everyone. Learning faster allows us to make better decisions and to build a shared mental model.

These are not bad things, they are very desirable properties and so should be engaged in and encouraged.

We might even find that all of these things are espoused in frameworks or philosophies that people parrot around engineering.

What is technical debt a debt against?

When we take a loan we are borrowing money from a bank.

But here there is no borrowing of money - value got released quicker and so more money was earnt. Growth was enabled sooner.

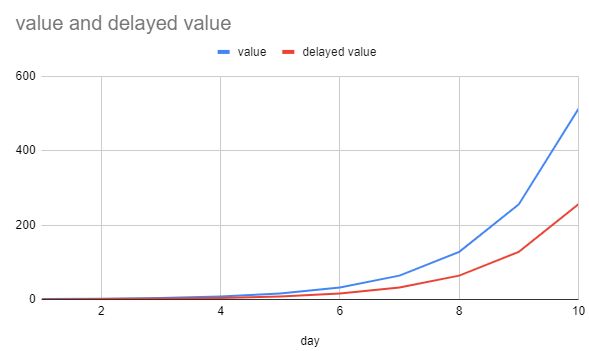

When we delay growth, we pay the cost of this every day for the lifetime of the project. IE a single day delay compounds into delaying every future piece of work by a day also. The delays stack to rapidly acumulate pushing all work out significant periods. The costs of these delays are accumulative and multiplicative in the sense that they compound in ways that reduce growth.

In a series where growth doubles every period the accumulating cost of delay is exponential. It is given by

total = value of day - value of day before total = 2^(d-1) - 2^(d-2)

… so a delay of 1 day at the start incurrs an additional cost of 256 on day 10 - even though the value of the delay was only 1 and only for 1 day.

This means that on the side of the people encouraging debt there is likley a geometric growth in the cost of delay over time. Can we find such a thing on the side that is exclaiming ‘technical debt!’?

The bank metaphor also doesn’t consider the amount of work the bank does to manage the risk of the debt and how it leverages this.

The debt here is against some imagined ideal, therefor incoherent metaphor

If we assume the debt we incurr can be reduced to ‘it slows us down for reasons’ then we can start to zoom in. We can break this into different kinds of debt later, but generally this statement is true.

But here the cost - ie the loss of value due to the delay that is being incurred - is not a tangible result. It cannot be measured or calculated, it is against a theoretical thing. It is a comparison to some ideal structure optomised for change - one that nobody can know until they know what the next change is, and even then, consensus is fickle.

Taiichi Ohno acknowledges this in his book ‘Toyota Production System’ where he talks about the need to be able to change the production system in order to be able to respond to the unexpected. Even in establishing demand for a new product, the customer doesn’t know what they want until they see what we build. Therefor we need to be able to change the production system in order to be able to respond to the unexpected. Lean principles build upon this by saying that we should be able to respond to the unexpected with a system that is more than the sum of its parts. To attempt to design against the imaginary optimial future is to miss the point of what is possible now.

IE when people say there is debt they are taking a narrow context and are saying if we ignored all other things except our ability to make the next change, then the system is suboptimal and we need to pay down the debt in order to make change quickly.

The problem is that this narrow context is not a helpful one - it is vague and not reality. It is not helpful to the business, it is not helpful to the engineers and it is not helpful to the customers. It is a fiction that is an oversimplification of something only implementors care about articulated in a way that is not useful to those who are not implementors.

Having a debt implies prediction of the future

So, on the one side we have incurring of a ‘debt’ (that enables the compounding effects of growth earlier) and on the other side, we have the expense of some migration towards an ‘ideal’ (ie undefined) piece of work that would not only of cost all the compounding effects but would also magically predict the future. It needs to predict the future because in order to realise the alleged benefits nothing unexpected can happen. Yet the number one rule of software development, particularly refactoring, is that the next requirement will make your last decision look silly.

If we could predict the future then we wouldn’t be having this conversation, we would understand what the optimal tradeoff would be - therefor there is something deeply incoherent about talking about technical debt in this way.

Egotism and Pride

This to me sounds like a hurt ego somewhere where someone wanted to make a pretty that did not line up with the reality of the situation. The reality is that we are not going to be able to predict the future and so we should not be investing in trying to do so. What is worse is that the business understands this - even if they don’t have the skills to articulate it. Thats why they made you ship the thing as soon as it was testable.

I cannot be in debt to your idealism that is divorced from the wider set of requirements that are relevant to good decision making. I reject this debt as your ignorance.

I cannot be in debt to your badly articulated currency - a curency that is at best an idea, at worse a construction that ignores the constraints and fails to find clever ways to exploit the opportunities presented by the reality of the situation.

I cannot and will not be held hostage to people who cannot articulate the value of doing something in a form that me (as your customer) can understand and value.

How should we talk about technical debt?

First, there has been no debt incurred. We have made a decision to release value sooner. This has been a decision that has been made in order to enable growth. Growth is good. Growth is enabled by value release. Value release is good. Therefore we have not incurred debt, we have made a decision that has a cost, and we will pay that cost in order to realise value and grow.

So what is the piece of work being described if it is not debt?

Quite simply it is a piece of work that will improve the ability of the business to make change given a specific sets of kinds of change and directions of change within those kinds.

‘We estimate that this piece of work will take 2 days, we think 50% of that time is waste. We think this because we have looked at data and know that we keep changing these parts (or work around soemthing). Additionally because we came back to this area 10 times we think we can gain 5 days in the next month where we expect to come back to it another 10 times. That is, if we spend a day fixing this now’

This is a conversation that you can have with the business / stakeholder. This is no longer about ‘technical debt’ it is about the ability to get through a backlog or enable growth. Its really that simple. It is also a no-brainer in this case, and as such is simply a thing the stakeholder + customer should be left out of. But being in teams that are managed at too a granular level is another problem - organisational debt (which again, should never be used as a term because of all the reasons in here).

We will shortly look at some tools and techniques that can enable a data driven conversation.

Make the change easy - then make the easy change

Software developers should be constantly refactoring and changing the code base.

A refactor is a change that has no behavioural difference - as measured by the tests against the system.

When any piece of work is picked up then first activity should be to refactor the codebase to make it easy to work. This is the same as organising a workspace to make it easy to work. That some teams have divested themselves of all responsibility to the extent that they have to ask ‘how can I write this code’ is a failure of leadership and management - as well as each team member not taking ownership of their workspace.

Different kinds of debt - drawing a box to then provide tools

- Adam Tornhill coined negligent debt as code that is not fit for purpose. It is just bad code that should not of been shipped

- Feathers defines legacy code as code that lacks tests - this is a different form of debt (perhaps a subset)

- There is fitness function debt - code that is not fit for all purposes, but meets a subset. Often existing tech debt approaches can be realigned to the business by thinking about specifying the problems to be addressed as fitness functions and then defining work to bring work in line with those fitness functions.

- Organisational debt - this is the debt that exists between teams adn departments. Engineers often want to fix these but unfortunatley this debt is actually ‘the way the business works’ - and so it is not a technical debt. It is really part of an organisational change programme - IE a new way of working that can be backed by a business case and adopted.

Examples of 4 would be using a shared datastore to avoid copying and deploying multiple stores. Later it may be desirable to seperate these - it would certainly make development of the seperate systems simpler. However this remains in ignorance of all the business process that will of crept in that specifically exploit the fact that the data store is shared and so can act as a communication medium between the disparate groups. The possible world of these being seperate feels like technical debt - but it is not. It is a now a business function.

Cases 1+2 are cases that should not exist anymore. These are produced by low quality engineering - these practises and culture should be addressed by the engineering team through communities of practise holding people to standards. You could call these standards fitness functions.

So If all is fitness functions and business value then what is the conversation?

The conversation is about the ability to make change. So we should be measuring things that effect our ability to make change in quantifiable ways. We do not want a qualitive conversation to be driving prioritisation - we want numbers.

The first thing to do is wrap the team in DORA metrics. This will give you some baseline metrics that you can use to talk about the business value of change. When we make a change or do a piece of work that is based around fitness functions for the team we should be able to predict the effect, measure it and then retrospect on the success of the change.

Adam Tornhill wrote an excellent book on this called ‘Your Code as a Crimescene’

In it there are several ideas - and diagrams that are quite easy to produce.

- He looks at what files change together.

- from this he can see coupling over changesets. He can then look for hotspots - files that change regularly

- From this he can see when files are changing together etc

3 matters because a file that is no longer changing has no value in being made ‘easy to change’. Some changes are seasonal - eg black friday.

This starts to build up a tool that can probe what is connected to what. This matters because the difficulty in changing things is knowing all the things that are connected.

The art of refactoring is to take a thing that would need many changes and change its structure so that you only need to make one change.

So instead of technical debt converations I have conversations about coupling and cohesion, I have conversations about how often things are changing and the number of people changing one thing for different reasons.

The goal of these conversations is to have numbers and diagrams that can show people what is happening and what the effect of a change will be.

Then later we can retrospective on the success of the changes.

I don’t ever use the word ‘technical debt’ - it is a distraction.