Sabotage! How to Design a Project Where Everything Will Go Wrong and Most People Won't Understand Why

Why write about sabotage?

Skip this section if impatient, it is introducing an idea for this series of blog posts, and why.

I have been trying to write a positive piece to explain what ‘good’ would look like, and it’s really hard because I don’t think there is a space that is good - it is more the space of ‘well we tried those things and found their tradeoffs suck, so now we are left with spaces and ways of working that avoid those patterns - and if they are required we deliberately choose them expecting, and so measuring and managing, problems’. Hopefully eventually I can write something positive and instructional - until then sarcasm and mercilessly pointing out self-defeating behavior will have to suffice. Not sure that’s inspirational though!

Its more an awareness that over there is definitely a swamp with monsters, but over here there might not be - or at least we haven’t found them yet. So we take the path of the least monstrosity until we have no other options - in which case we can deliberately choose what kind of monsters we face.

Unfortunately, paths with monsters are often made out of gingerbread and shiny things (simple explanations that don’t consider the whole system). We just need to aspire not to be childish and know that there are consequences and that we can play the game better by being very deliberate about how and when to face monsters.

This is as opposed to most projects where ways are decided based on either a) copying the thing from before b) reading a blog post (the irony is not lost). For b) we should find small scale ways to test by finding the low complexity, low competitive-advantage part of a domain and experimenting there (explanation shortly). Not decide to reposition a project by choosing the Spotify way - that Spotify moved away from more than a decade ago (This was a model based on Alister Cockburns' work from 10 years prior to that, same guy as Hexagonal Architecture and Crystal Methods).

Maybe this is an age thing - I have worked on more than 40-50 projects in 20 years. Maybe I have more points of reference and just f****d things up more than others. I don’t know why this stuff stands out to me but is seemingly hard for others to see - that is, until you show them and then they become believers. So this stuff is hard, but also critically important to get better at.

Additionally, we are not in a space where there is best - and I don’t want to imply I know best - but we are in a space where other options are just empirically worse and over time we learn more and more about how things break when they are combined. There is so much room for innovation and improvement but we take crappy off the shelf solutions (both process and product) as a substitute for reflection and hard work. What we can learn is, structurally, why they go bad because it is quite easy to reason about structures and constraints - it is much harder at individual work item level. It is also easy to devise experiments per work item if we adopt this perspective.

Essentially the TLDR of all these sabotage posts is that neither off the shelf tech nor process will ever solve you specific businesses problems. How could they? You may be able to solve low advantage high complexity problems through them but unless you are a business that has nothing unique about it nobody elses product is going to solve your unique hard complex problem. You have to do that work yourself - it’s why you exist, it is a good thing and something that should be leant into. Some cost is actually directly correlated to value - most is not. When we forget this we perform the sabotage in here - name;y constraining everything to a single delivery method.

So I am going to write a series of things about how to really destroy productivity in ways that are really hard to unpick and debug later as a kind of bestiary of things that we really should avoid - and by avoid I mean we actually have to do homework of analysis to find creative ways to avoid them. This is not easy and is a constant piece of work

So, how shall we sabotage? what do we want to happen?

Honestly, if I was to try and take down an organisation, this method in here is what I would do because nobody would see me coming - and many would see the ‘common sense’ of these suggestions whilst being utterly oblivious to what was about to happen.

So what do we want to happen?

- We want to make it look like everybody is busy but tie everything together so much that every change causes change everywhere

- We want to make it so that it gets exponentially harder to achieve anything over time

- We want the project to be late, suffer overruns and essentially exploit time and materials

- We want the people who are causing the problem to have no idea and blame others

- We want to infantalise as many roles and deep experience of a domain to maximize alientation.

- But we also want to do this via a means that looks ‘obviously good’

So we want chaos (in the Eldrich sense), we want stuff to go wrong, time to be wasted, wrong work to be done. We need to break the communication structures in ways that produce coupling at a distance so that it is hard to detect. Turns out that sense making frameworks also can be used for evil.

By Tom@thomasbcox.com - Own work - a re-drawing of the prior artwork found here (File:Cynefin_as_of_1st_June_2014.png) that incorporates more recent changes, such as renaming “Simple” to “Clear”., CC BY-SA 4.0, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.p…

From Cynefin, we know that the best way to throw systems into unexpected complexity is to over simplify. It is to deliberately mis-categorize something complicated, complex or chaotic into clear (or something complex into complicated). This works because when we over-constrain nuanced systems into overly simple rules then the rules will fail. The more we couple to the rules that will the worse it gets. The best part is that most people will wrangle their way out by introducing more rules because that is the only move they have! Therefor if we pick some simple rule(that sounds reasonable) and couple everything to it (such as a single process for all delivery) then we know carnage will ensue. The only thing people can do to compensate for the bad decision is to add more rules into the system - because removing rules, whilst being the right answer, is a highly counter intuitive move. This is particularly true if we do this in a place where there are many possible ways of doing something.

So we want to take something complex and over constrain it - and package it up prettily to sell the idea that it is in fact simple with a guranteed outcome if only you turn the process handle a little bit more.

Instead of having multiple ‘rules’ or an understanding that we cannot know all the answers we are going to find something nuanced and try to put it into a single box, a way.

The sad thing for me is that this (upcoming way) is simply a default for the majority of projects I see, and it is a great example of over simplification causing everyone to behave like they are stupid because of deliberate design choices in the system. These are not stupid people, we have simply designed a system that gives them 2 apparently stupid choices.

If you play a game and the options for your next move are

- walk into a wall

- turn around and walk into a wall

then people will walk into walls - or stop playing the game. This means we are also left with people who are happy to walk into walls. Let that sink in! We can build a self-reinforcing system of sabotage if we are lucky! We can design a system of people who choose to walk into walls all by themselves given sufficient time! (and when you recognize this happening in systems, it truly feels like this is what people are doing - it is highly depressing)

The cost of this is that all the time in a project gets eaten up by processes that are not about building the deliverable. All the time consumed here represents less time to build, but also a much later starting point for building the right thing that will be released.

It is a regular thing to ask why code hasn’t been done on time. The code likely took a few weeks to write on a ticket that traces back to a request made a year before. All that other stuff delaying? That is waste, so how can we maximise that waste in a subtle way?

If we measured gross lead time and broke this into the cycle time of the parts (instead of vainly adding up arbitrary cycle times - and thus missing out parts) then all this would be visible which would enable people in the system to make decisions to remedy the problems. So please, do not measure gross lead time.

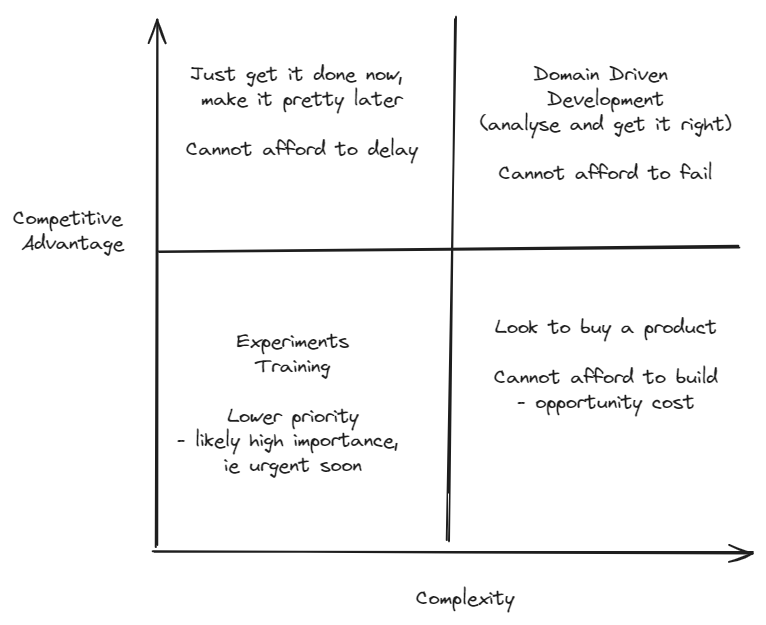

Target: Complexity vs Competitive advantage tell us we need multiple delivery strategies - lets use 1!

After the sabotage example we will come back and explain the 4 quadrants but first, want to get into hat it means to have 4 quadrants like this.

Greg Young is the first person I saw draw this (over a decade ago) as he was using it to describe the scope within which event sourcing would make sense. He did a lot of pioneering on event-driven, CQRS and event sourcing architectures

This diagram enables us to simplify picking a family of strategies based on 2 dimensions every organisation should know prior to deciding on a delivery strategy, product strategy and so team structures.

But what can we sayi? It is telling us that if we do not have, at least, 4 families of delivery strategies we are being overly simplistic because we should see that we really do want to work in very different ways depending on the problem. This is one thing I like about Crystal Methods and Alistair Cockburn’s way of thinking in general. He has taken the observations on coupling and cohesion that led to hexagonal architecture and applied them to different contexts - which is exactly what i’m trying to do 20 years later.

The sort version of explaining this diagram: Top right: Hard, complex and highly valuable - also very hard to copy. Other organisations have to build this too - it is not commodotized. Here you should be building because you are pushing into the future. Bottom Right: This stuff is also complex, but it also doesn’t give you an advantage - likley because it has been commoditised. This means you should be looking to buy an off the shelf product. If you really need to build this you should also be willing to sell it as a product - AWS pioneered this via dog-fooding its cloud to serve its ecom business. Top Left: High advantage and not too complex - these systems can be replaced. Low cost fast processes should be prioritised. Bottom Left: Low advantage low complexity: these are good places for learning, training and helping underperformers reach their potential. Potential buy, but often this just increases complexity for no reason. Just write some simple replacable cheap code.

By Tom@thomasbcox.com - Own work - a re-drawing of the prior artwork found here (File:Cynefin_as_of_1st_June_2014.png) that incorporates more recent changes, such as renaming “Simple” to “Clear”., CC BY-SA 4.0, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.p…

What does overly simplistic mean? In Cynefin when you treat a complicated domain in an overly simplistic way (ie as a simple domain) you will follow a recipe when there i a need for expert opinion. This will cause mistakes which will reveal themselves as surprise. Surprise is the key characteristic of complexity - it is discovery of constraints that were unknown. Therefor an overly simplistic approach takes a domain in Cynfin and moves it towards being complex. This is a bad thing - unless you want to actively discover new ways of working.

What it is saying is that when you build a thing, if you understand its value vs its complexity then we discover that there are at least 4 different strategies - ie WAYS of working, ie Delivery approaches that we can use - and so should be using in every project as a default.

Here value of work is the articulation of how doing ‘a thing’ will influence the relationship of customers with clients in a way that effects client investment into future work. Value is not just delivery of a thing - that is insufficient to be useful. It requires the statement of how the full circle is expected to work with expected numbers.

It’s not like we can all be Rothko, there are more colours than 1. Even he changes up the colour sometimes. Lets, exploit managements desire for easy to understand in the hope that they learn! (they won’t because there will be so much going on that piecing it all back together is a lifetimes work)

We can take a space where we know multiple approaches are needed and instead sell a single approach because we also know this will sow the seeds of chaos whilst also appealing human desires for simple answers in a way that will fuel itself getting worse and worse.

To be clear the opposite to this is to build healthy teams of humans that you can trust to go do the right thing, give them direction (more of x, less of y) - not targets, keep open communication and let the highly qualified people make decisions in a small pocket (to limit blast radius) and then encourage cross team continual improvement to watch the maturity grow.

Or, you can keep your kids locked inside with locked down tablets because you are afraid and then complain later when they don’t talk to you and are ‘addicted’ to tablets and ruminate on how you used to play outside and get into all kinds of trouble. Yes, I did that too - its the same thing except here we hired professionals with loads of experience and then infantilised them.

Sabotage 1: Insist on a single top down delivery approach for the whole thing.

So what is the first way to completely screw up an organisation? - well we simply obliterate context by dictating an approach by using an off the shelf solution (Spotify, scrum, a single product for all problems, whatever).

We justify it with things like ‘best practice’ to shut down any ‘complainers’, we are ‘easy to understand’ enjoyers. We then say we need to all work the same way so that we can move people around and have standard best practice processes (as if this whole crazy game we play has been solved) because then non-believers can be used as straw-men to fuel a fire of confirmation bias.

It’s funny that these processes that advocate this approach get names that imply risk reduction. One key part is that this is to ‘enable comparison of team performance’ but in reality it is a freezing of current process into permanance. This is the opposite of what data-driven or learning organisations want, it is the shutting down of an organisations ability to learn and change for itself. Probably perfect in some industries but definatley not one that is fundementally about delivering learning systems into organisations so that they can orientate themselves to change in directions that enable growth.

The whole notion of wham-bam-thankyou-mam we start, build and then we are done with no future no changes to software can only make sense in a business that doesn’t want to change. This is because software is simply an electronic way of connecting people and as their relations and communication needs change, so does the software.

We need to optomise for cost of change, not cost of build

What is never talked about is a comparison of gross lead time before the change to gross lead time after the change. That would let the cat out of the bag - so definitely don’t do that. Instead, track the cycle time of each work station and insist they reduce their time. That will cause another layer of havoc as they all unwittingly destroy each other (via quality) whilst making the numbers better. If you wanted to measure this surreptitiously you could monitor backlog size, in fact you could use this as another vanity metric. Maybe I should pull those 2 out as separate examples of sabotage later - they are powerful.

But back to the current sabotage:

I start with this as I think >90% organisations are making this overly simplistic mistake.

By doing this, you will appeal to leaderships desire for simplicity, it will have a very clear and easily to articulate message that people can buy into, and they will start to repeat it to their supervisors as progress.

It also maps onto Atlassian' desire to subvert all your processes and desire to tie you into their ecosystem of products for complex concurrent delivery in software - that for the last 10 years at least cannot cope with 2 people working on the same thing at the same time - ie concurrency. Perhaps this is a lesson for future posts (this will be title something like ‘Taxi-Rank is the best way to destroy teams’). Honestly, though if the company that is selling you methods cannot fix their concurrency problem are you really sure that their methods should be adopted or their software used? They cannot do the thing they are selling - method to manage multiple concurrent processes. The irony. They either do not use those methods or they can’t make them work either.

The cost of single unified delivery model will be that everything ends up being invested into like the top right corner of the diagram because that is the part that demands the most analysis, and so process.

By creating a single delivery approach everything ends up in the one single approach - which is the same thing as instead of having a structured thing made of seperatley deliverable parts everything ends up as a large single bowl of stew.

The cost of this is that we are taking ‘experts’ and we are vastly reducing the set of decisions they are able to make. As a result thinking stops, assumptions stop being tested and delivery rot sets in.

This happens because if we do not design in discriminating factors from the start then sub-units of the organisation are never going to have the data they need to make the right decisions. It is a tremendous amount of work to change this - there are a lot of cultural transformation pieces as a result. This kind of problem manifests all over in different ways. Really organisations that realise this late missed the critical design goal of their system - how do we enable people in all parts of the system to independently make measurable decisions to benefit the whole?

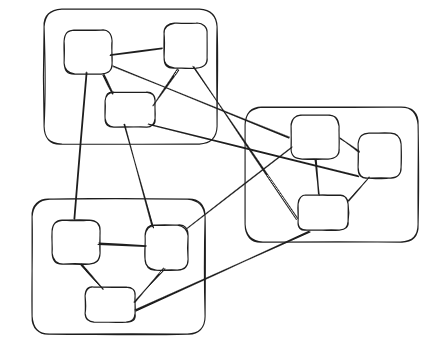

This stew produces a low-cohesion high-coupling relationship between teams of teams

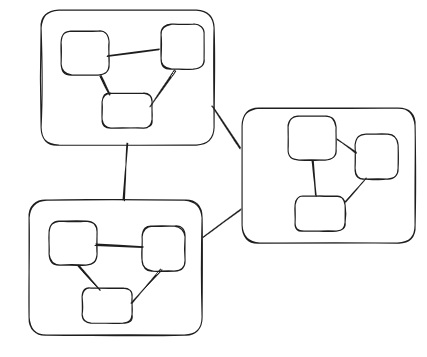

What we want to be encouraging is the diagram to look like this - but this depends on finding discriminating factors and building proper boundaries which would produce a structure like the following

This is really a form of organisational debt, stemming from the sabotage, because it is a lack of cohesion due to a lack of boundaries and a tightly coupling because the lack of boundaries makes it possible (and so inevitable simply due to entropy and constant cost of keeping them separate) for everything to get mixed together.

In engineering there is a really bad pattern from 10 years ago in microservices where we would physically deploy the services separately - this was to force the separation. These days we take a more moderate approach of a single deployment with logically separated services. If you ever work with me and see me wanting to merge 8 teams into a mono-repo with a single delivery pipeline, it is because I have identified this problem.

Don’t get me wrong, I love stew because when I eat I want that lovely mixing of all the things. But when I am building stuff I want concrete separate dependable blocks that can be delivered in isolation (and so simplicity - less complex) and so far more predicable because we hate surprises. IE rather than homogenous mush I want to have a neat plate with no sauces infringing on my meat - thankyou very much.

Everything will be analysed and understood in depth before starting because that is the necessary process for work that cannot afford to fail - it should be noted that the vast majority of work could fail, because we can control how they fail (if we choose a delivery strategy that embraces learning rather than rigid progress) - which will be next on the list.

However, a single delivery process also defines the same failure process, and so we lose this set of decisions.

The cost of doing anything rapidly becomes the cost of doing the most dangerous thing (because it’s the same process everywhere, so everything looks the same) which either cripples our ability to move fast when necessary but also attempts to strip diversity by producing fungible parts.

But worse, if we imagine 4 things (one for each quadrant) doing a single delivery approach will let those separate things become entangled - and ultimately delivery of one of them without the others will become impossible (read staggeringly expensive and very, very late).

This is because it is not possible to validate the parts without the whole - due to lack of cohesion and high coupling. This is ultimatley the emdgame of a single delivery process - to cripple all teams by forcing them through the single merging of all work into a single test framework thereby producing a single mega team in effect.

Now delivery of the entire program is constrained to the delivery speed of the slowest part.

This is all a technically a priori (it wasn’t for me in discovery, as I am not a genius, it is counter-intuitive), and so I know I can ask 2-3 questions and identify exactly what is going wrong.

It follows because of the allowance of low cohesion into the system which given enough time will cause each part to depend upon each other in a circular dependency forcing the only time validation to take place to be ‘after’ teams have ‘finished’ and so are on other work.

This is what software architecture has evolved to solve - it is time to start architecting delivery and product with people who properly understand this stuff because the cost of getting this wrong is engineers getting put into horrendous conditions over and over.

If you want systems to be designed like this fine, but I don’t want to work with you. We can do better.

Summary

This is a process that is simple on paper, but produces extraordinary complexity over time - and this is the main reason why I see public and private sector projects costing eye watering amounts of money (Construction and tech are my primary experience points). The methods of finance lead to multiple vendors which causes services that are related to contracts rather than any end to end customer focussed problems - this is low cohesion against customer value being coupled across engagements. It gets worse when clients move vendors about.

As a result, these projects are characterised by having layer (technology teams) based architectures because there is nothing left to split teams on - i.e. specialisms. If you can’t be arsed to (or won’t let people, or don’t have people that know how to) split your product into independent value streams then it follows that it is logically impossible for any one team to validate that their stuff works without waiting for others to also finish and deploy and then depend upon a battery of tests that neither of them can own properly. This is because all the different features depend on every single layer working together to work.

IE layer based architectures demand (there are a few exceptions - but these depend upon sequential work following dependency chains) external QA teams writing external tests which implies that nobody else is able to know if what they have done works. This is a very silly situation. We cannot say we are done if we do not know it works - but we cannot be done until everyone downstream is finished? The paradoxical outcomes resolve themselves easily with buggy and defective integrations which cause over budget and late projects.

Removing the ability of teams to verify their own work and creating a super team of coupled teams cannot be a desirable design goal - this is why this is the first entry in the Beastiary.

I can honestly understand everybody making this mistake once. But I am seeing experienced people repeating this over and over. It is driving me mad, the bar for ‘satisfactory’ is well below what I am willing to tolerate - because the impact of this is engineers working late, being under the gun for building complex things with no time. Many leave the job. Sure it’s stressful for leadership but at the end of the day they are on the sidelines shouting ‘encouragement’ at teams of people playing a game that’s rigged against them by the people ‘encouraging’ them.

This is such a colossally stupid way of working because it undermines each teams ability to deliver independently - essentially all the separate teams are really part of 1 giant super team (because that is the unit of acceptance) but nobody is tracking work at that level (gross lead time) and so nobody can know how to make their stuff work. So these teams spend their whole time playing Jira game saying they are ‘done’ but not ‘qa done’ … which is the same as saying ‘well we wrote some code and have no idea if it works - but that is the way the delivery and product teams defined done, so it’s not our problem’.

The number one rule of engineering is - do not start writing code for a thing unless you can clearly define what winning is. When you break this you have no way to know when to stop and how to evaluate what you have against winning. But the teams in the above situation will end up getting tickets that don’t fully define what winning is in the global context, only in the local sub-component context which no customer or client cares about (because value)

Agility, quality and high release rates depend upon independance. It is not possible to have independence whilst you depend on another team to validate - your constraints become that teams constraints (especially when multiple teams feed into them). This is what the single delivery system achieves - it undermines independence by indirectly enabling high coupling in strange ways. It is the perfect evil mastermind plan.

This is how modern day evil looks, it is mass stupidity constructed via systems designed to fail from the ground up. When you are in the systems everyone has the best intentions and genuinely wants to win - but nobody seems to realise that they are playing a game that is designed to make them lose.

It causes me great anxiety watching this - even more so because people are so busy wasting time on fake work that doesn’t make it to production in these systems they cannot stop and help themselves.

I will write up more examples of sabotage methods - but they will all have a very similar theme. At the end of the day it is about creating low-cohesion, highly coupled systems and cackling away as everything goes wrong.

So, do you want your project to be a bowl of stew or a nicley organised plate?

So, its easy to throw shade, but how should we look at this? So quadrant by quadrant:

So, the quadrants

Generally all work moves through stages - some work can move from top left to top right once constraints are discovered. But also work can move from top right to top left if constraints are violated (eg budget or time).

However, generally, if we ignore messing things up, work doesn’t move about and can roughly be categorised into these quadrants.

If we do need to move work around more a better tool to discuss that is Wardley Mapping - the 4 columns in that map pretty well to 3/4 of these quadrants. The bottom left does not. This is a tool I would use whilst discussing and planning migrations / transformations.

The Bottom Left - aka graveyard

This is the work that will be very important but can never quite be prioritised to the top of the pile.

This is the work where if it fails doesn’t carry a high cost of failure.

This is the place where we are safe to try innovative ways, where we can train people in the ways of working.

It is the place where you can put lower performing teams / people without paying a hefty price.

Failure here can produce work that is urgent - but until then it is the place for incubating ideas about how to work and testing technologies in a responsible way.

Bottom-Right - Hard + expensive to build but not main mission

This is the quadrant of buy somebody else’s commodity.

If none exist, consider a pivot to build this and then expose as a product for your main idea to consume.

A really good example of this is HR systems, Service desks, accounting systems.

This work is often best characterised as simple or potentially complicated in Cynefin.

There is not much to say here beyond that the delivery methodology here is primarily a set of integration specialists - this required a very different set of processes to say inventing something new that nobody has seen before (top right) because the work is complicated/simple. The domain is well understood with contexts categorised by another company. We simply have to consult to find the right approach and then implement it by following instructions - this is the simple end of the scale.

We do not want a methodology that depends upon heavy design and user research rounds. Instead, we want to validate the behaviour of the dependency against their documentation. We have the instructions.

Turning projects that are primarily integrations into complex beasts is just unfortunate because they lose track of the fact that all their constraints in method, delivery and product scope are all coming from the integrations. I have seen several companies fail due to this mistake.

Top Left - JFDI - aka cannot afford to delay.

This quadrant is what startups often live in - but every organisation has work in all these quadrants.

There are a few ways of explaining this, major program people will have S curves (which maps when taken holistically) which imply different behavior at different profiles, but the best, I think, is Kent Becks 3X explore, expand, extract because this also incorporates the idea of convex and concave economic risk payoff, but I can also see transition between different parts of Cyneffin and constraints analysis in here also.

Work here is growth in an organisation driven by marketplace competition i.e. time (or shrinking budgets). So we can convert work in the top right to be this quadrant by delaying! Imagine having something complicated and valuable that cannot afford to be analysed!

This work is critical errors as infrastructure is found inadequate, unexpected or market opportunities with a deadline or mass customer influx due to market fit. Several organisations have dedicated people who wander around communal areas making themselves available as problem solvers or clinics to enable this - they tap into the informal network rather than some structured process.

This work is simpler in some ways (I like it here because I can roll from emergency to emergency without needing to manage a calendar) because the cost of delay of doing nothing is insurmountable and so people can easily understand that a probe-sense-respond approach makes sense. Because growth, we don’t actually know the answers - often we have problems nobody has experienced before, we just know we need to do something and the best way to do something is a very cheap probe to see what happens and then either double down or find a new probe.

Here the goal is to do small rapid iterations in order to learn without overcommitting

The reason why a lot of organisations discovered throughput (And then lost it again after) in covid was because ‘lives were on the line’ so all the bullshit got cut out. There is no reason why the effectiveness of this work should be put on a shelf because we want to ‘do it properly’ IE sabotage by insisting on a top-down delivery model that everything fits within (because its ‘easier to manage’ - at the cost of being able to deliver).

In Cyneffin this is also a complex domain - it is one where the constraints are not understood. It is necessary to invest in it whilst this is the case to discover the constriants we do not yet know of. It is complex because we often cannot afford to spend the time to discover enough so that it becomes complicated. This is because if it is complicated, and we put experts on the work then their intuition will be right and if it is wrong then we were right, it is complex. It’s a freeroll, but it requires us to work in a very specific way to exploit it like this.

- low investment experiments with predicted results to direct future decisions (raise, call or fold)

- Very high level of experience of people - the problems here are urgent and will be at the very edge of knowledge. Potentially in the space of genesis - Wardley

Again, the way of working here should be very rapid iterations of small scale experiements. We cannot take months of a product cycle. These things end up being ‘tech driven’ and are best done as ensemble teams so that everyone who can input and decide is present at all times.

During growth there is eventually too much friction of change (which slows everything down) and this is when it is necessary to factor out the complex-high value domain and design it, i.e. converting it to top right work. Because it is only after a bit of growth do you finally understand the actual constraints you should be designing for.

This is why we need domain experts in these teams.

Most of the time teams jump to domain design based on whimsical estimates - this is why startups and small businesses that are spun up from someone who has deep industry experience with vision stand a much better chance of survival. They have years of headstart in constraint discovery.

This gradual migration right due to slowdown of constrain discovery is how an area that was once complex for an organisation can become complicated.

The techniques that work very well here are Hypothesis driven design with TDD and Extreme Programming with continuous deployment and feature flagging to decouple behaviour from deployment (because we cannot wait to turn things off). We also need ways to deliver behaviour to subsets of users. The goal is to eliminate all the faff and get to iteration loops that can be measures in hours from inception to deployment to customer-client feedback. Teams in this space should be taking ideas and deploying them to production multipple times per day - ie their gross lead time should be hours. Normally I see a GLT of months - but we deploy multiple times a day

Top Right - The big complex vision

So far none of the stages have involved a heavy expensive analysis process. 2 have been ‘just ship it already, we can work the problems out later’ (but for different reasons) and the other is ‘can’t somebody else do it?’

Take that heavyweight ‘agile’ process that takes 6 months to ship anything

This is the quadrant that represents real innovative value that is hard for competitors to copy. It is the stuff that differentiates from other organisations because a) it is valuable b) someone cannot just come along and commoditise it easily (think AWS).

To build this part of a system it is required to have people with significant domain experience from multiple perspectives.

When someone comes to me with a startup idea this is the part I am looking for them to tell me about - otherwise (eg they are a Chat GPT wrapper) someone else can and will come along and duplicate it producing a simple race to bottom on cost optomisation and marketing efficiency. It is a highly vulnerable position and not one I would be willing to invest in.

This part will include relationships with external people in key parts of the intended business - customers as we like to ambitiously call them.

This is the part of the system where I will sit down and produce proper information models, boundaries, contracts, collaboration mode and map use cases against number of users. The goal here is to identify ways to taking one large complicated problem and break it into 2 or more smaller complicated systems that have independant behaviour.

The danger here is that we start to think that we can design everything before we start. This is not true because we are still interacting with customers. Customers change their behaviour - dramatically - for reasons that are beyond our control. This feels like suprise! IE we are still in a complex domain.

So we still need an experimental approach - so what differentiates this from the top left. In the top left if we don’t fix it we destroy our growth prospects, the thing just won’t work. Over here we are all about maximising marginal gains or solving deep algorithm problems that will enable leaps forward.

The urgency is often slightly lower because the long term payoff is often dramatically higher.

However, this is still a part of the system where we should adopt experimental methods - we just have different levels of tolerance for what we expose to more and more people to than the top left. In the top left we cannot afford to wait, in the top right we experiment because we cannot afford to be wrong.

IE agility here completely depends upon identifying slices, those users and finding ways to deliver to some and not all of them. So we still need to decouple behaviour form deployment.

Why do so many projects design decoupling behavior from deployment out?

IE we still should not favor a heavyweight system because we cannot afford to invest 6 months of project expenditure to find out if we are wrong or not. We need to use creativity to identify ways of getting faster feedback by releasing subsets of behaviour to subsets of users and having defined fitness functions around scaling.

Eg a system for people interviewing other people can be broken down into several parts

- calendar management for interviewer + interviewee

- Some kind of an interview process

- some kind of feedback process

I would then realise that these 3 thing might then get moved to different parts of the quadrants - calendar management sounds like a largley low-advantage high cost thing to build - so buy it. IE we can take our top right ‘domain’ and analyse it into high-cohesion:low-coupled lumps and then apply the quadrant analysis to each.

E.g.

- The interview process is likley top right, and so we would look to properly design that process

- Feedback process is also likley a hybrid of top-right but also some parts that can be bottom-right, pushing into some commoditised product.

So a single lump gets broken into parts that can each be evaluated in the quadrants.

I personally use Domain Driven Development in this space - but a lot of product practices also map.

The key thing here is to identify value chains and design around them rather than technologies.

Wrap up

These quadrants are powerful heuristic tools.

A note should be made that all work can end up in the top left if we mess it up too much. My opinion is that because of this the way of working in the top left is likely the way we should be working in other places - but with different fitness functions controlling the percentage of users who see it.

The difference is that in the top right we need to properly achieve 2 things

- division into independent value streams to organise teams end to end around

- building on this identification of use cases form users (that will fall on a power curve) and to therefor be able to build very small slices and test them with small populations of the slice in order to have a fast feedback cycle without having to build say 50 pages of a web journey before anyone can do anything.

There are lots of ways to get small fast delivery - I will be writing future article on more ways of sabotaging teams from every achieving them!

A lot of those ideas though have already been covered - we can just repeat the same tricks all over to really screw things up though!

Needless to say - building distinct seperation in teams based upon value stream enables highly cohesive systems that can have lower degrees of coupling.

You know you have got this wrong very simply - everything will take longer than you expect, it will fail more often and when you do release you will see lots of production defects from use cases that cross boundaries that go beyond the simplest possible test.